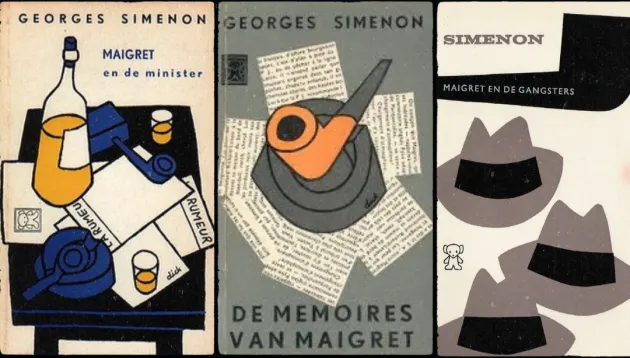

The Maigret novels by Georges Simenon

Published on 1st December 2023

Georges Simenon, who was born 120 years ago in the Belgian city of Liège, lived an eventful life and was a prolific author. He wrote 75 novels and 28 short stories about his most famous character, Jules Maigret or, as everyone (including his wife) calls him, Maigret. While I consider myself a latecomer to the Maigret novels, having picked up a copy of one for the first time in 2020 (at the ripe old age of 31), I am, like many converts, a zealous one.

In the novels, Maigret, a burly, overcoat and bowler hat-wearing, pipe-smoking, police inspector, investigates, and invariably solves, murders. While we learn tidbits about the inspector and his colleagues over the course of the books, we remain largely ignorant of his personal life — such as his relationship with his wife or what he does when not working. Despite this, we do learn about the character of Maigret. For example, in the course of an investigation, the inspector will drop into local bars and, depending on the time of year and his mood, drink wine, calvados or beer and chat, coerce, charm and often bully locals into giving him information on his latest case.

While I can’t speak for other fans, the overriding pleasure that I derive from reading about Inspector Maigret is the familiarity. There is a comfort, a warmth even, in the familiarity of a Maigret novel. Without fail, Simenon hits each of his marks as the novel proceeds. A murder occurs. Maigret is informed. Maigret and his officers are completely in the dark about who committed the crime. There are several suspects (or none at all). Maigret thinks about the case, visits local haunts, intimidates or cajoles potential witnesses. He puts himself in the place of the killer. Somehow or other, through his brilliance and psychological insight, the case is solved.

This warmth is in sharp contrast to the actual subject matter of the books. Without fail, a character is murdered for money or love or, sometimes, for nothing at all. The people that the inspector meets and interviews are rarely happy or content. Rather, they are hateful, greedy or unbearably lonely. Interestingly, the inspector rarely has contempt for those he encounters. In fact, one of the most endearing things about the character of Maigret is how little he seems to judge those unfortunate enough to come into his purview.

This refusal to judge is likely due to the unorthodox life lived by Simenon himself who once said that “my motto…[is] the one I’ve given to old Maigret…‘understand and judge not’”. Understanding is at the heart of the Maigret novels. For those who can’t understand my fascination with such a deeply unfashionable character all I can ask is that you judge not. For the intrigued, why not join me in celebrating 120 years since Simenon’s birth by opening a Maigret novel and deciding for yourselves.

Peadar, Libraries IT