When Dublin telephonists challenged the government

Published on 28th May 2019

It is frequently claimed that the EU gave us equality, and certainly it has helped to have Equal Pay and Equal Treatment Directives, but it was frequently women workers who forced the government to implement the improvements in their employment conditions to which new legislation entitled them. If laborious industrial relations procedures did not deliver for them, the women were quite prepared to take to the streets to insist that they be treated fairly.

It is frequently claimed that the EU gave us equality, and certainly it has helped to have Equal Pay and Equal Treatment Directives, but it was frequently women workers who forced the government to implement the improvements in their employment conditions to which new legislation entitled them. If laborious industrial relations procedures did not deliver for them, the women were quite prepared to take to the streets to insist that they be treated fairly.

In the 1970s the public telephone exchanges could provide jobs with steady, albeit low pay and the expectation of a pension if a woman stayed until retirement. As it was generally expected at the time that marriage and child-bearing would be a woman’s primary role in life, the poor terms and conditions were not a deterrent if one was only thinking of being in the job for a few years.

In the early 1970s, pay discrimination between men and women was institutionalised in both the public and private sectors. The government introduced the Employment (Equal Pay) Bill in 1973 but claimed that they could not enact it because it would cost too much. They appealed the Equal Pay Directive that came from the EU in 1975 but were told that they would have to pass the Anti-Discrimination (Pay) Act 1974, which the Minister for Finance had tried to defer until 1977. RTE’s Seven Days programme marked the introduction of equal pay with a report shown on 11 July 1975. They found that in the Civil Service and the Public Service the gap between male and female pay rates had actually increased, despite the Directive from the EU.

The Post Office Workers’ Union (POWU) held an Equal Pay Telephonists Symposium in October 1976, which had its biggest ever attendance of female members. The largest delegation was from the Dublin Telephones section and the average age of the delegates was early to mid-20s. In March 1977 the POWU Executive gave authorisation for several two-day strikes in the Dublin Exchanges. Their intention was to draw maximum public attention to the way they were being treated without totally crippling the telephone service. By 1979, their claim had been recognised by the Labour Court but was still not implemented by the management.

One of the notable aspects of the press coverage of the various industrial actions conducted by the telephonists was the involvement of journalists who reported extensively on the way the women were being treated. The journalists’ support elicited a lot of public sympathy for the telephonists because it meant that the unfairness of their treatment was revealed to people outside the exchanges.

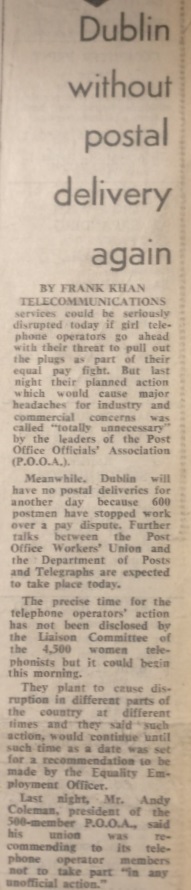

Irish Independent, 8.1.1979

The Department of Posts & Telegraphs finally made the equal pay settlement in February 1979. There was a fairly widespread belief at the time that when a wider strike began within a week of that payment, that the Department did not expect the women to support their male colleagues in lower grades when they went on strike for a long overdue pay rise. That turned out to be a very wrong assessment. The telephonists went out en masse and remained out for the full nineteen weeks of the strike, although they had nothing to gain for themselves.

Dublin Central Historian in Residence Dr. Mary Muldowney