Statue of King William III

Published on 5th February 2019

Dublin supported James II at the Battle of the Boyne, but following his defeat by William III, a protestant ascendancy resumed control of the city and began to forge links with the new and successful monarchy. This process intensified after the death of Mary II in 1695 left William III as sole monarch. Dublin Corporation added William’s arms to the City Sword in 1697 and in the following year, the king presented a chain of office to the Lord Mayor of Dublin, carrying the monarch’s bust on a medallion, which is in use to this day.

Dublin supported James II at the Battle of the Boyne, but following his defeat by William III, a protestant ascendancy resumed control of the city and began to forge links with the new and successful monarchy. This process intensified after the death of Mary II in 1695 left William III as sole monarch. Dublin Corporation added William’s arms to the City Sword in 1697 and in the following year, the king presented a chain of office to the Lord Mayor of Dublin, carrying the monarch’s bust on a medallion, which is in use to this day.

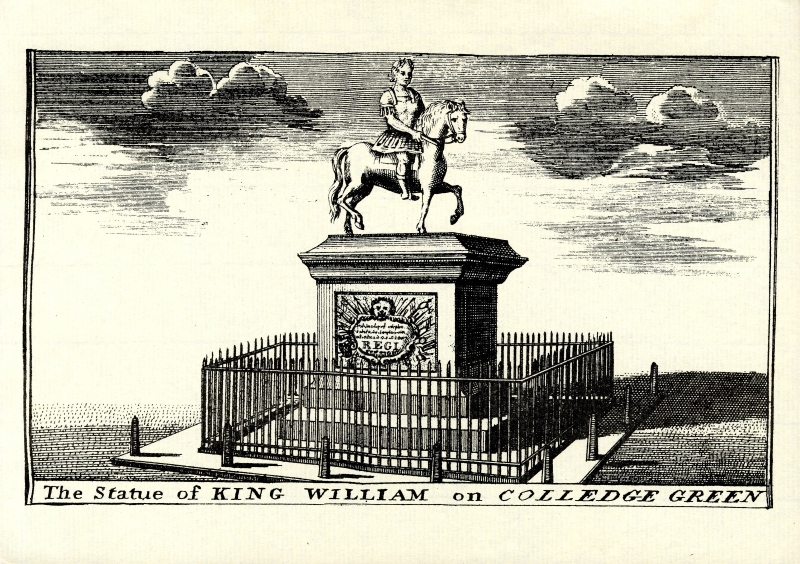

But these expressions of loyalty were not sufficiently public for the City Assembly, which early in 1700 decided to erect a statue of the king, to be placed on a pedestal in the old Corn Market.[1] From the inception of this project, the Assembly was aware that the statue could become a focus for protest by Jacobite supporters, and decreed that it should “be defended with iron banisters”. [2] Two Dublin merchants, Henry Glegg and John Moore, who were on business in London, were asked to commission the sculptor Grinling Gibbons to execute an equestrian statue of the king in copper or mixed metal and a contract was signed on 9 April 1700.[3] In fact, the statue was executed in lead. Gibbons was to be paid £800 sterling in four instalments: £200 on signing the contract, the same again two months later, a further £200 when the statue was shipped off, and the final £200 when the statue had arrived and was in position.[4] The Assembly then decided that the statue should be placed, not in the Corn Market, but in a more prominent location, in College green. It was also agreed that the stones of St. Paul’s gate in the city walls, which had been demolished by alderman George Blackall, should be used to make a pedestal for the statue.[5] The statue was unveiled on 1 July 1701, which was the 11th anniversary of the Boyne (following the Julian calendar in use at the time). The lord justices, who were guests of honour, were “entertained by publicly running out some wine” – presumably so they could have the fun of watching the populace scramble for a drink.[6] The event became a yearly one, with a parade around the statue, and volleys of muskets fired in the air. Some security was afforded to the statue when the city

Plumber, Alexander Erwin, was paid £13-0s-9d for “fastening the iron work around the king’s statue”[7] and this afforded adequate protection to the monument for the best part of ten years.

This honeymoon period ended in 1710. The City Assembly was informed that on Sunday 25 June “some persons disaffected to the late happy revolution, did offer great indignities to his late majesty, king William of glorious memory, by breaking and defacing some part of his statue erected on College Green”. [8] In fact, his sword and truncheon were broken off. The lord mayor, Sir John Eccles, believing that the attack was fuelled by drink, ordered that a “strict inquiry be made in the several public houses what guests were [there] at unseasonable hours” on the evening of 25 June.[9] The authorities at Dublin castle offered £100 for information and the city offered a further reward of £50, which was claimed by a local man, Richard Markham.[10] The guilty parties were Trinity students who were expelled from the college. But attacks on the statue continued. In October 1714 a truncheon, which was in the king’s hand, was broken off and removed and in 1715, the year of the first Jacobite revolt in Scotland, the Corporation decided to build a watch house beside the statue and post a couple of sentinels there.[11]

Protestant sentiment continued in Dublin throughout the 18th century. The position of William III’s statue outside the Parliament House, made it a focus of the Volunteer rallies which took place in College Green in the 1770s. The Lord Mayor’s Coach, which was commissioned by the Corporation and built in Dublin by William Whitton, was carved with unionist symbols, including orange lilies to honour William III. The Coach was first unveiled on 4 November 1791, when it led a procession to mark the Birthday of William III – a procession which took place each year thereafter. Equally, there was a Catholic reaction, and in 1798 the sword was removed and an attempt was made to saw off the kingly head. In 1805, supporters of Catholic Emancipation covered the horse with a mixture of tar and grease, while in 1837 the figure was blown completely off the horse. [12] It is said that Surgeon-General Sir Richard Crampton, who was a tremendous snob, was at a dinner party in St. Stephen’s Green when a distraught man came to the door looking for him and saying: ‘You must come quickly Sir – a most distinguished gentleman has fallen off his horse in College Green!’ Whereupon Sir Richard rushed off – to find king William’s statue prone on the ground![13] On this occasion the statue was repaired by John Smyth, whose father was the more famous sculptor Edward Smyth.

(Plinth of King William's Statue)

The statue of William III continued to excite controversy well into the 19th century. In 1842, city architect Hugh Byrne recommended that the cut stone base and iron railing around the statue were so defective that they should be removed and replaced and the finance committee was instructed to do so. [14] In spite of these precautions, the statue continued to suffer physical attacks necessitating repairs, which were conscientiously carried out: in 1843 alone, such repairs cost the City Council more than £73.[15] But after the Home Rule Party seized control of Dublin City Council in 1880, this careful attention was not applied to the city’s statues and in 1888 they were reported as being dirty, with William III’s statue also being dangerous. [16] A report about the statue in the following year, found that it was indeed dangerous, with the horse in particular having sustained several cracks with a likelihood of it falling into the street and causing injury. The City Engineer recommended that the statue should be repaired – at a modest cost of £35 – and that a new site should be found for it at Foster Place, away from traffic.[17] It was also suggested that a plaque should be added recording that the monument had been restored by the Corporation of Dublin during the Mayoralty of the Right Hon. Thomas Sexton. However, although the repairs were carried out, the statue remained in College Green. Even though the City Council members were largely nationalist, there was no suggestion that the statue should be removed altogether and a proposal from John Erskine of Belfast, offering to purchase it, met with the abrupt rejoinder ‘The Statue is not for sale’. [18]

[1] Anc. Rec. Dublin, VI, p. 232.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Surviving works by Gibbons in Ireland include a monument in St. Patrick’s Cathedral Dublin to Narcissus Marsh, archbishop of Armagh, and two in Kinsale, Co. Cork to the Southwell family. See Edward McParland, ‘A monument by Grinling Gibbons’ in Irish Arts Review (Yearbook, 1994), pp 108-9.

[4] Anc. Rec. Dublin, VI, p. 235.

[5] Ibid., VI, pp 237, 239.

[6] Anc. Rec. Dublin., VI, 248-9. The lord justices were Henry Moore, 3rd earl of Drogheda; Narcissus Marsh, archbishop of Dublin; and Hugh Montgomery, 2nd earl of Mountalexander. T.W. Moody, F.X. Martin, F.J. Byrne, A New History of Ireland, IX, (Oxford, 1984), p. 491.

[7] Anc. Rec. Dublin, VI, 256.

[8] Ibid. VI, pp 416-7.

[9] Ibid., VI, pp 416-7.

[10] DCA, MR/36: Dublin City Treasurer’s Account Book, 1651-1717, fol. 622b. Markham was paid £50 ‘for discovering the Persons that did Deface the Statue of King William’ but their names are not given.

[11] Anc. Rec. Dublin VI, pp 540-1. This pattern of attacks on the statue of William III lasted throughout its history. It was finally blown up by the old I.R.A. on 11 November 1928, the 10th anniversary of Armistice Day. Dublin City Council disposed of the shattered pedestal in 1929, as it was judged to be a hazard to traffic.

[12] Cliona Cussen, ‘Public Sculpture: a cautionary tale, or Ni Neart go baint da cheile’ in Sculptors Society of Ireland, vol. 10, no. 4, 1989.

[13] Frederick O’Dwyer, Lost Dublin, (Dublin, 1981), p. 27.

[14] City Council manuscript minutes, vol. 11, pp 185-6.

[15] Ibid., vol. 12, p. 146.

[16] Dublin City Council minutes, 1888, item 180

[17] Dublin Corporation Reports, 1889, vol. 3, pp 61-2.

[18] Dublin City Council minutes, 1889, items 257, 281