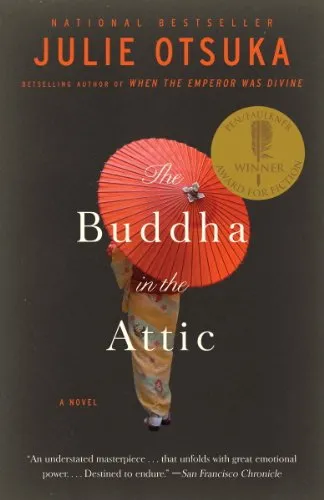

Staff Pick: The Buddha in the Attic

Published on 14th May 2024

The Buddha in the Attic by Julie Otsuka tells the story of a group of ‘Picture Girls’, young Japanese women who, in the early decades of the twentieth century, crossed the Pacific Ocean to the west coast of the USA, to enter into arranged marriages with Japanese men already living and working there. The name ‘Picture Girls’ refers to the fact that these young women had only ever seen a photograph of their future husbands before departing from their homes to spend the rest of their lives with them.

This is a slender little book, comprising eight short chapters which chronicle the course of these women’s lives from their initial voyage across the Pacific sometime around the end of World War One, to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour and the subsequent unleashing of an American xenophobia that ultimately resulted in the forced internment of all Japanese-Americans by their own government.

In a fusion of broad sweeping generalities and precision detailing of the mundane, each chapter charts a different aspect of the lives and struggles of these immigrant women in their newly adopted homeland, from slaving in the fields, farms and kitchens of their white neighbours, to raising their families, to dealing with the seldom distant racism of pre-war USA.

Rather than tell the story through the reassuringly conventional use of a first or third person narrator, that single named individual on whom we focus and to whom we can relate, Otsuka opts instead to tell the story from the group’s perspective, eschewing the use of any central characters and adopting the first-person plural as her narrative mode, thereby allowing a group of women who were robbed of their voice, to speak together with one voice.

In doing so, Otsuka frees herself from having to filter a narrow overview of history through a single story, instead introducing us to many stories simultaneously, thereby giving us a much richer view of history simply by providing so many voices to respond to it.

Some of the stories are deeply moving and some are humorous, but all are threaded through a hauntingly elegant narrative of unfaltering empathy. History flows ceaselessly through the pages, but Otsuka’s near-invisible layering of information is so succinct and graceful that I soon found myself catching glimpses of individuals among the lines, a brief flash of recognition before they promptly merged back into the whispering hum of the crowd.

Otsuka has infused her book with a rhythm all its own, a rhythm generated by a rigorous economy of words and phrases and almost total lack of metaphor or description, and this rhythm swept me forward until I was utterly immersed in the plaintive voice of these near-forgotten women, whispering down through the decades to remind us all of their struggles, their suffering, their lives.

If the power of Otsuka’s writing lies in her restraint, then her genius lies in getting us to care about an almost forgotten group of nameless people from the past.

What does the Markometer say? 8.5/10

Submitted by Mark Carter, Cabra Library