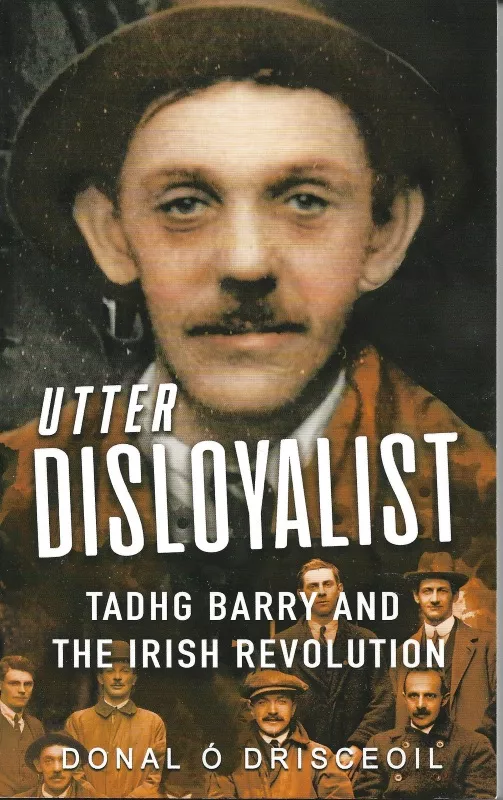

Utter Disloyalist: Tadhg Barry and the Irish Revolution

Published on 24th January 2022

A decade after writing a pamphlet about Timothy (Tadhg) Barry as “a foretaste of a longer, book-length biographical treatment”, Donal Ó Drisceoil marked the centenary of his death in 2021 with a book examining the life and times of a man described by the author’s UCC colleague John Borgonovo as “a socialist whose revolutionary career was dogged by sheer bad luck”.

Tadhg Barry was born in Cork in 1880 and educated locally before obtaining work as an asylum attendant. After a spell in England, he returned to Cork and worked with the newly established Old Age Pensions Board. By this time, Barry had Gaelicised his name and immersed himself in Cork’s Irish-Ireland movement and separatist organisations such as Sinn Féin and the Irish Republican Brotherhood. For a while, he switched allegiance to William O’Brien’s All-For-Ireland-League and became a Poor Law Guardian but later broke with the party over its backing of the British war effort in 1914.

Barry was an enthusiastic supporter of the Gaelic Athletic Association and along with the likes of J. J. Walsh helped to reform and revitalise the GAA in Cork, training teams, acting as a referee, and writing about Gaelic Games under the penname of “An Ciotóg” (the left-hander or clumsy person) in addition to his other journalism. In April 1916 Barry’s book Hurling and How to Play It, the earliest publication of its kind, appeared in print for the first time.

A member of the Irish Volunteers’ Cork City Battalion D. Company, Barry was arrested in late 1916 for “seditious” comments made during a Manchester Martyrs commemorative event. He was imprisoned at Cork Gaol from January to July 1917, going on hunger strike towards the end of his incarceration and writing poems, verse and ballads that were published as Songs and other (C)Rhymes of a Gaol-Bird.

In May 1918, Barry was arrested again as part of the “German Plot” and sent to prisons in Wales and England until March the following year. Although this latest imprisonment was difficult, Barry’s spirits were kept up by the remarkable growth of Sinn Féin and transformation of the Irish political landscape during the period.

Within a month of his release, Barry became a full-time Cork organiser for the expanding Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union and served as the branch secretary of the Cork No.1 (James Connolly Memorial) Branch. A syndicalist who admired James Connolly, Barry was also a devout Catholic and considered Jesus Christ “the greatest Socialist of all”.

In January 1920, Barry was elected as an Alderman for Cork Corporation on a Sinn Fein/ITGWU ticket. One year later, he was arrested with other republican councillors, again without charge or trial, and after seventeen days at Cork Gaol and a few days at Spike Island, endured a harrowing journey to Ballykinlar internment camp in County Down.

It was in this bleak and sandy setting, the first and largest of the British internment camps set up during the War of Independence, that Barry lost his life. In the run-up to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the British began releasing internees on temporary parole. On 15th November 1921, as Barry stood with others at the camp fence to wave goodbye to some departing comrades, he hesitated when a young sentry called on the group to retreat and was shot through the heart. He was 41 years old.

The Cork man proved to be the last high-profile casualty of the British crown forces during the War of Independence and the scale of his funeral suggested that he would be afforded the same martyred status as Tomás MacCurtain and Terence MacSwiney. Instead, to quote Ó Drisceoil, Barry’s name became “lost in the smoke” after the Irish Civil War.

Utter Disloyalist allows for that smoke to finally clear, a welcome development as Tadhg Barry, described in a British Army intelligence report a century ago as “a notorious and irreconcilable revolutionary, who has taken an active part throughout his life in every rebel and revolutionary movement in Ireland”, deserves to be better known.

Dr James Curry is a Dublin City Council Historian in Residence (North West Area). Last year, he taught a series of workshops on the lives of Tadhg Barry and Diarmaid Fawsitt for the Cork City and County Archives entitled ‘The Blarney Street Revolutionaries’.