Building description

Building description

Composition

The dwelling is mid-terrace with a two-storey-over-garden level basement, and original four storey return. It was built on the west side the road, c. 1880, as part of the development of a six house terrace. Unusually, there is a timber frame extension (from the mid 1980s) at rear ground floor level projecting over a yard with matching steps down to the garden.

The front façade is set ~11m back from the road which allows a flight of shared steps to the hall door and features a two-storey bay window at basement and ground floor levels. It is a solid wall structure faced predominantly with red brick. Its decorative programme includes polychromatic brick to window and door arches and two mid-storey double strings, a granite ledge at ground floor level and granite and polychromatic brick forming a cornice and frieze at the top of the projecting bay and at eaves level. The bricks are machine-made. While they were originally wig pointed (as can been seen on the neighbouring house and in sheltered parts of the case-study house), most of the façade was re-jointed in a struck cement joint during the 20th century; the reduction in aesthetic quality can be seen clearly by contrasting the arch lintels of narrow windows of the two neighbouring houses.

The one-over-one sliding sash windows appear to be original, and there is a simple, Georgian style, arched fanlight without glazing bars. Its glass may be the only non-clear float glass in the house. The cast-iron grillage on the parapet of the bay appears to be in good condition. There is a slight bulge evident in the brick piers of the ground floor bay window which is common but should be mitigated.

Interior as built

Architectural features in the hallway and two reception rooms – principally timber floors, architraves and moulding, windows and shutters – are in good condition. It is interesting to note how different the skirtings and architraves are to those in a typical Georgian Dublin residence. It would appear the reception room fireplaces and hearths are not original given the lack of agreement between the timber trim at the hearth and the stone hearth itself.

There are fewer architectural features internally on the other floors. Architraves in the basement are simpler and may or may not be original. Flooring and skirting throughout the basement are modern ceramic tiles. The original running cornice of the top floor can be seen within the attic as the ceiling was dropped at some stage, presumably as a way to reduce heating bills (as this reduced the volume of air to be heated convectively in those rooms). It would be relatively easy to recover this feature to those rooms as original ceiling joists are still in place – improving attic insulation and general airtightness would compensate thermally for the recovering of the original room volume.

While clearly a modern intervention, the timber-frame extension has considerable charm. As its thermal performance (airtightness and insulation levels) can easily be improved by accessing ceiling and wall buildup from within the room and the projecting floor buildup from below, there is no reason why it shouldn’t provide value for years to come.

Changes since construction, existing condition

|

Item |

Description & comment |

Heritage Impact |

|---|---|---|

|

Physical impact of creating multiple occupancy |

There was likely already a garden-level entrance in place. Instead of removing the internal stairs to the basement, the previous owners had installed a door at the head of the basement stairs. |

Low |

|

Services and moisture impact of creating multiple occupancy |

Sub-division duplicated the number of boilers, cylinders, central heating systems, water supply, kitchens etc. In short, significant complexity was added to the dwelling’s plumbing and pipework bringing greater maintenance onus and potential failures |

Low - moderate |

|

Attic and joists |

At some stage, possibly during the First or Second Oil Crises, the ceilings of the top floor were lowered, resulting in two sets of joists. The original running cornice is still in place. The layers of joisting complicates the insulating of the attic |

Low - moderate

|

|

Rear timber frame extension |

In building this a portion of the rear wall of the house was removed. The extension, which is unapologetically of its time, shades the basement level below. It may be regarded as historic in its own right (being possibly 30 years old) and has charm. |

Moderate |

|

Rear door |

A Scandinavian pine door (10 to 20 years in place) is arguably the leakiest window or door in the building. |

Low |

Tenancy

The garden-level basement was previously rented as an own door-accessed flat with use of a limited area of the rear garden. The current homeowners have returned the house to single usage. As a result of the previous split use, there are still two heating systems, three shower rooms and two kitchens. Without question, great efficiencies can be wrought by an energy efficient retrofit, including a rationalisation of services, in this context. The owners moved into the house in July 2013 – at the time of interview a few months later, they hadn’t yet experienced a heating season so couldn’t comment on winter-time thermal comfort or energy efficiency.

There has been an increase in recent years in the number of period dwellings returning to single-family ownership all over the city centre and inner suburbs. This is partly due to falling commercial rental value for period houses (as more suitable office space become available elsewhere) and legislation which effectively banned the poorest kind of bedsits. Dublin City Council has recently done significant work in providing guidance for owners of townhouses in the South Georgian Core on how to return those buildings to residential use in a sensitive manner. However, the housing of each era or construction type will present specific issues, weaknesses and opportunities.

Bay window structure & drainage

The small flat roof still has its original waterproofing of a soldered lead sheet. Presumably this sheet sits on timber boards, on the ceiling joists. It is hard to see how much of an upstand it has around the perimeter or what condition it is in. A surprisingly small outlet drains water down into the joist depth and out to a narrow drainpipe; see images of the flat roof of the protruding bay and of the front elevation. On the left side the stub of the original lead pipe can be see pushed aside by a modern plastic one; on the right side, an older replacement pipe in galvanized metal can be seen. It is unclear whether or not a small hopper (within the depth of the joists) takes the flow from the flat roof before discharging onwards. It is an area prone to a lack of maintenance (due to limited accessibility) and therefore vulnerable to leakage. The only way to insulate is within the joist depth. A talented plasterer could make invisible any opening made for that purpose through the central flat portion of the bay’s ceiling. The 19th century Albany Road case study (Albany Road #1), features a best-practice approach to draining this small roof [link to follow].

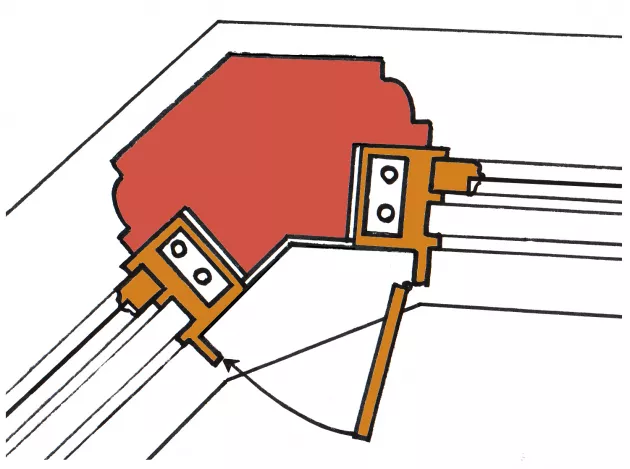

In common with many of Dublin’s Victorian and Edwardian houses, the design of this brick-built bay structure has an inherent flaw in the way structural loads are transferred to the ground. Some rotation has occurred at the junction at which the portion of wall above the window head sit on the piers below. There is not enough movement to require rebuilding or immediate remedial works, but it is certainly something that should be assessed and stopped from progressing. As can be seen in the diagram, the brick pier is irregularly-shaped in plan: it is possible that the load of the heavy parapet is distributed eccentrically, resulting in it having an outwards and a downwards thrust. A ring beam (as found in many modern constructions) or ring chain (as found in many traditional church spires) would prevent this but (as usual) is absent here. If the mortar joints on the room side of the pier were poorly installed or had a weak mix they may also contribute to this movement through compression: inflexible cement jointing on the outside might exacerbate this further.

The good news is that noting such issues at an early stage allows them to be dealt with through relatively minor remedial works. An engineer with experience of traditional buildings should be consulted. A range of works might be specified and detailed, such as repairing the rear joints of the piers or tying the parapet together with remedial stitching rods. In any case, the preservation of the original high-quality building fabric is paramount.

Pointing and aesthetics

The lime joints in this 1880 terrace were pointed in a style known as wig pointing (see image). It has only recently been established conclusively that the decorative lime pointing used in Dublin, known as wig pointing, is quite different from the tuck pointing used in Britain. ‘Wig/Tuck A Research Project on Historic Pointing Techniques and Façade Finishes in Dublin’ (a body of research completed in 2010 that was commissioned by DCC and Heritage Council) explores this in detail. Wig pointing is to be found in common usage in Dublin for all but the most functional of buildings from the early Georgian period right up the start of the First World War. Many of the case study houses in the current body of research were originally wig pointed.

Comparing the brick arches over the narrow side windows of the canted bays of the case study house and its attached neighbour (see image), one can see why wig pointing contributed greatly to the aesthetic quality of historic brickwork and therefore historic dwellings in Dublin. Coloured mortar (the wigging) covers both mortar and brick edges to allow a narrow lime or painted lime protrusion to be visually read as the pointing. While wig and tuck pointing partly arose to conceal the non-uniformities of cheaper handmade bricks and the wider joints they required, they gained a cachet of their own. Considering wig pointing’s near ubiquitous use in Dublin up until the First World War it is clear that it was widely considered to contribute a sense of quality to a façade long after the use of machine-made bricks (with far sharper edges and smaller tolerances) made its concealing nature unnecessary.

It would nevertheless appear that this concealing nature was used to allow a lower specification in the construction of the narrow arches, as seen in the image. Normal bricks instead of voussoirs (shaped bricks specially made for arches) have been used: the wig pointing that may have had a purely decorative function elsewhere on the façade seem to have been used to conceal widening mortar joints here. Whatever the reason, the wig pointed arch on the right looks far more attractive than the crude cement jointing on the left.

Attic, ceiling and party wall

The attics of the case study house and the attached neighbour to its right were originally common: modern, lightweight blockwork has closed the voids to either side of fire breast, see images taken within the attic. It may be that on this small terrace the houses that share common entrance steps also shared attics.

As with many domestic attics, detritus has been allowed to accumulate. As attic hatches are small and as attics never get seen by visitors and owners don’t like spending time in them, old water tanks, discarded pipes, lengths of timber, fallen parging plaster, dust etc., often remain in place. Homeowners tend not to see how these items obstruct the ability to both insulate and achieve a good level of airtightness there. Cleaning an attic is an essential step to insulating it well. In this case, two levels of joists complicate work in this attic further. Even if it meant temporarily removing some breather membrane and roof tiles to facilitate the removal of material, the owners would benefit greatly from following the advice in the section on Getting attic insulation and attic

Moisture, leaks and ventilation

On progressing downstairs to the garden-level basement, the smell of detergent becomes discernible: clothes are regularly left to dry on racks in the front basement room. The owners are concerned there may be some rising damp in the basement: mould spotting can be seen in a cupboard of the rear basement room. In addition, there is a high level of moisture evident in a defined strip of plastered wall for several metres just above the tile skirting in the basement hallway.

The basement rooms are sporadically heated by the heating system and receive little heat from the sun due to shading of the bank of steps to the front and the overhanding timber frame extension to the west-facing rear. By regularly drying clothes in rooms with the coldest surfaces – where a suspected water leak is also present – the occupants are adding greatly to the basement’s moisture stress. They need to find an alternate strategy to drying their clothes. Could a clothes dryer be the solution in winter and drying on clothes line in the garden or under the extension be the solution in summer? Ducted clothes dryers work better than condensing dryers but generally require a hole cored through a wall.

The moisture staining above skirting level is likely to be a burst pipe. In the best case scenario, such moisture results in damp spots on the walls that are impossible to decorate and may give rise to mould or rotting skirting; a worst case would see such a release of water resulting in an undermining of foundations, especially where internal walls of older houses sat on timber plates on compacted earth or sand.

A non-invasive survey could narrow the area of investigation to a limited area of floor, but an area of floor would have to be dug up in any case. As the floor, floor finishes and skirting are modern there would be no heritage loss with an invasive inspection or complete replacement. By combining maintenance work with insulating some, or all, of the basement floor there is a long term financial gain (reduced bills) and an immediate gain in comfort (warmer surface temperatures) and hygiene (lower potential for condensation and mould).

Initially, the two most important actions are to (a) find and seal the leak and (b) allow the masonry to dry. It is a mistake to redecorate before moisture content is reduced for the depth of the wall – not just on its surface. Removing skirting and the area of plaster with elevated moisture content is advisable. Blowing air vigorously across the surface over an extended period is a far more effective way of removing damp than use of a dehumidifier.

Air leakage

The air permeability of the house was measured at 10.64 m3/m2.hr: this value may not be concerning given the large thermal envelope (1.5 times larger than the floor area), the presence of two intermediate floors (the perimeter of which is often the least airtight portion of wall) and the high level of air leakage measured in the mid-1980s timber frame extension. While the sliding sash windows and various junctions of this extension were common points of leakage (both easily improved), the modern Scandinavian pine door giving access to the rear garden from basement level had a higher level of air leakage than any other door or window in the building. It whistled when the dwelling was pressurised above atmospheric pressure.

Context

The road, which is unified by the street line and predominant use of redbrick, charts the development from the domestic architecture of early Victorian Dublin, featuring Georgian style plain elevations and parapets, to mid-Victorian architecture of modelled elevations, bay windows, polychromatic brickwork and eaves. The west side is characterised by small terraces (including the case study dwelling) and semi-detached houses to individual designs suggesting numerous smaller builders. The east side of the road is more architecturally coherent with fewer changes in design and typology, which suggests larger developments by fewer builders.