Building description

Building description

Composition

The case study house is a Type-E cottage, built in 1886 for the Dublin Artisans’ Dwellings Company (DADC). The single-storey, three-bay row cottage opens directly onto the public footpath. There is a slight camber arch over the door and flat arches over the windows. The façade has a painted modern napp render finish on pebble-based mass concrete walls. The render is in reasonable condition with minor repair needed. The reveals to window and door opes are square edged with embellishment. While some neighbouring cottages now feature patent reveals, a close inspection of the elevation of the Type-E cottage in the Irish Architectural Archive show these are not original (see image). The windows are arranged as top-hung casements over fixed light made of non-thermally broken aluminium. The panelled entrance door is also modern. The step and window sills are original granite. The foot scraper to the right of the door, and cast iron wall vents to either side are also original. The underfloor vents are partially obstructed by render and paint.

The painted timber fascia (fixed to the masonry in lieu of full eaves) is in need of replacement. Electrical power and broadband cables jostle untidily under the gutter. A modern plastic downpipe has replaced the cast-iron downpipe. It drains the original cast-iron T-junction (shared with adjoining cottage) onto which a modern half-round plastic gutter sits loosely. The A-profile pitched roof of the original structure has a natural slate roof with terracotta ridge tile. A stamp identifies John Browne & Company of Bridgwater, Somerset, as the supplier of the ridge tile. John Browne & Company traded between 1859-1894. A brick chimney stack with feature corbelling rises from the ridge above the left party wall. It houses two flue pipes, one for each property.

The detail shot (see image), taken on the adjoining Kinahan Street, shows the irregular nature of this early example of mass concrete, featuring pebble aggregate and brick infill. The render and plaster coats of this 8” wall play an important role in retaining its integrity.

Interior as built

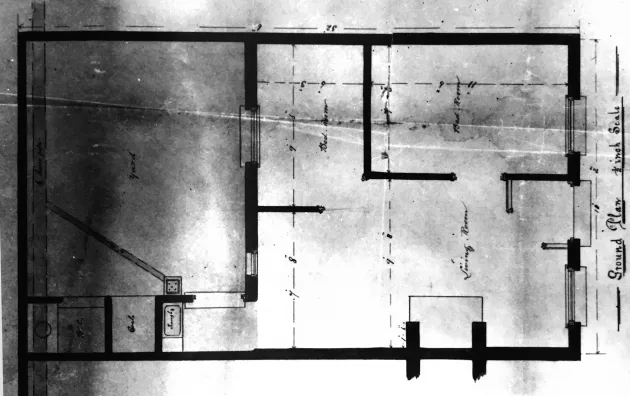

The current floor plan and the original floor plan from the DADC file in the Irish Architectural Archive are both provided in images accompanying this case study. Both show the entrance door opening into the small wind lobby then into the irregular-shaped living room. Clustered around this room is a small double bedroom, a single bedroom and a tiny scullery that doubles as a lobby to the rear courtyard. The plan is very tight, especially when one considers that many of these cottages were home to large families. The left side of the hearth provides space for one or two small armchairs; the right side may have been the location of the table, near the scullery. The DADC drawing shows a small window that would have provided some light to the table: its blocked ope was recently uncovered by the new owners.

The original mantelpiece was replaced some decades ago by a smaller, mid-century glazed tiled concrete surround. The removal of wallpaper has revealed older coats of paint that show the mantlepiece was ~1.5 m high. Decades of gloss paint layers have been peeled back to reveal the original joinery (see image), which is now more than 130 years old and generally in good condition. To the rear of the house, some floorboards have been cut back due to significant levels of rot. The skirtings must also be replaced due to damp, but the internal doors, door frames and the door and window architraves can be reconditioned and re-used. These give a charm and authenticity that new joinery could not replicate without exact copying.

The mass concrete walls rise as party wall gables within the attic but stop short of the roof soffit. It is unclear how many attics on this terrace are open. This is a significant concern in terms of fire safety and must be rectified. The mass concrete walls of the scullery, and the coal store and privy behind it, are all still in place. They were incorporated in a jerry-built extension that was built over the existing yard floor in the early 1960s. The recessed cast-iron gully and the dishing that drains the floor of the yard to the gully are still in place. The latter runs into the floor void of the extension: this is discussed in relation to changes since construction below. Layer upon layer of floor coverings, wallpaper and paint testify to fashions across a century. These are hard to remove where walls are dry but have literally fallen off the walls to the rear where moisture ingress had occurred.

As with other Type-E and Type-C cottages and the Irvine Terrace case study, this small dwelling has high ceilings (~3.1 metres). The height is valuable in small dwellings as it gives a sense of space, even drama: the large air volume also contributes to better indoor air quality: see comments below. As walls are always more expensive to construct than cut rafter roofs, the consequence of a requirement for high ceilings and tight budgets is the construction of relatively low walls and long sloped ceilings to front and back, these are known as a coombed ceiling in Scotland. The lathe-and-plaster ceiling is cracked in places but may be salvageable: this is discussed in the proposed works. During inspection, it was necessary to cut a hole in the ceiling to see into the attic. It may not have been inspected since it was built or the slate roof was repaired. The parge coat lining the roof slates, which would have provided wind tightness, has completely collapsed. This loss may have contributed to the thermal discomfort that the tenant felt some decades ago, evidenced by the works then carried out.

The original generous ceiling height remains in the bedrooms. Sometime in the 1980s, the ceilings were covered with expanded polystyrene tiles to improve thermal comfort. Perhaps at the same time, a new ceiling was installed in the living room about 400 mm below. Original internal doors (tongue, grooved and ledged) were modernised behind sheets of wallboard. In various places, gun-applied foam and pieces of cloth were stuffed into corners and under skirtings to prevent heat loss due to air infiltration; metal woven foil was stuffed into small gaps to prevent vermin ingress.

Additional comment – air volume

The large air volume in the livingroom (due to its tall ceiling) is valuable in a small dwelling as it can buffer moisture produced by the occupants, or cooking or washing activities: small volumes are more sensitive to moisture generated in ‘wet’ rooms (kitchens and bathrooms). Equally, lime-based lath and plaster has excellent moisture buffering characteristics and with its alkaline chemistry is a biocide to mould. Multiple layers of modern wallpaper and paint would have reduced this capacity. Many homeowners in nearby developments have lowered these ceilings to gain a loft bedroom. While understandable as a move to increase space, the lower air volume and non-hygroscopic or non-biocidic surface liners may result in poorer air quality.

Additional comment – fire safety

The party – or separating – walls to either side of the case study dwelling stop short of the roof covering. Albeit an existing, original condition, this does not comply with modern Irish building regulations. The lack of fire compartmentation puts occupants of all affected dwellings at risk of fire breaking out in a different dwelling.

Junction of compartment wall and roof - The junction between a compartment wall and the roof of a building should be capable of restricting fire spread between compartments. A compartment wall should be taken up to meet the underside of the roof covering or deck and fire stopped where necessary at the wall/roof junction… The gap between the wall and the underside of the roof should be as small as practicable (generally not greater than 50 mm) and be filled with suitable fire stopping material over the full width of the wall. Section 3.2.5.11, Technical Guidance Document B - Fire Safety

It is therefore necessary that whatever works are proposed for the dwelling they include the completion of the two fire compartment lines. This work is likely to involve building up the wall with lightweight blocks and mortar and use of fire stop in the zone between roof finish and top of masonry wall. The re-roofing works will facilitate this, albeit the re-roofing tends to happen quickly due to weather concerns. The works will require the removal of part of the lathe-and-plaster ceiling.

Additional comment – impact of jerry-building

The dishing in the floor of the yard drains rainwater from the yard itself, the extension’s flat roof and the rear portion of two cottage roofs in under the floor of the extension (see images). The Belfast sink in the scullery, the washing machine and the modern pressed metal sink at the rear of the extension also discharge directly down onto the gully. Incredibly, all this water flows openly into the gully less than six inches below the modern finished floor of the extension. The dishing and gully must have regularly blocked due to accumulation of moss and detritus. The dishing would have allowed an easy path for vermin. A removable (well-screwed down) floor panel testified to the need for maintenance. It is inevitable that water will spill over, wicking into the masonry walls, rotting the timber grounds that support the floor and feeding mould. The thermal comfort and indoor air quality experienced by the last occupant must have been poor. On arrival, the new owners could not walk on the partly collapsed floor of the extension and found original floorboards in the rear bedroom that had been cut back due to severe rotting. The house smelt of damp, mould and rot.

Context

The development is bounded by Infirmary Road to the west, Jerome Connor Place (a stable lane to the rear of large Victorian townhouses on North Circular Road), O’Devaney Gardens to the east and Montpelier Gardens (an 1929-30 DADCO development) to the south. This is one of the most densely-settled parts of Dublin with a housing density of ~86-91 dwellings per hectare. The plot of the case study dwelling is 5.53m wide from centre of party wall to party wall and 10.00m deep (measuring front of façade to rear of garden wall). Courtyards to rear of each one-storey cottage were designed to occupy ~1/3 of plot: while many remain, most have been reduced by at least half due to the addition of extensions containing small shower rooms and kitchens. When built the internal area of the dwelling would have been 30.4 sqm (including partitions walls and scullery, but excluding cold store and privy). When purchased with extension the heated floor area (including partitions walls) was 41.9 sqm.

The development contains a variety of house types. The two terraces facing Infirmary Road feature open pediment gables, which address the street and are repeated on their adjoining gable walls. The pediments are expressed through four courses of corbelled brick. This pairing of pediments is repeated on the gable wall and front façade of the four houses forming the junction of Aberdeen and Sullivan Street. The pairing re-occurs at the far end of these terraces and unpaired open pediments face each other at the start of the 21-unit long terrace beyond the junction on Aberdeen Street. The corbelled brick detail seen in the pediments is echoed in the chimney stacks of both the Type-C and Type-E cottages.

Hierarchy is signalled in a number of ways within the development. The four gables facing the major road (forming the external ‘façade’ of the development as a whole) are supported by shallow brick pilasters that corbel off the façade at the height of the first floor window sills. The bottom of the open pediment doubles as the capital of the pilasters. The result is a subtle evocation of a classical temple front. On the gable walls at another major junction, large chimney stacks protrude to the same extent as the pilasters, supported on corbels at the same height. Half way up the stacks are recessed blind opes. The gable walls of the next line of cottages feature another partially protruding chimney stack, but these are narrower and corbel out from the line of the base of the open pediment. The gable walls at the far ends of the front terraces are brick with a third type of protruding stack. Finally the gable walls at the far end of the other terraces mark the start of the long terraces of rendered single-storey cottages. Appropriately, these gable walls are also rendered save for the brick pediments overhead. The architectural language of the development is an exposition of the values of Victorian Dublin – stratified, conservative, mercantile and at times very elegant.

The Type-E cottages are simpler with few architectural features. The most obvious feature today is the brick detailing of the chimney stacks. The original tongue and grooved doors are simpler than the six-panel doors of the Type-E cottages and have a smaller fanlight overhead (see drawings). The camber arch over the door is a subtle reference to the importance of entrance over window. Without doubt, the key architectural feature of the cottages was intended to be the windows. These are metal with the upper portion opening on a horizontal pivot. The complex pattern echoes a chinoiserie bamboo screen. It is likely these windows would have cost more than the sliding sashes of the grander Type-E houses. The appearance of these windows along a whole terrace of cottages must have appeared quite ornate. Given their architectural significance, for what are otherwise modest cottages, it is a shame that so few are left. The windows in the photograph (similar to those in the drawing) had been removed from a cottage in a nearby street in lieu of modern windows. The current owners asked for them, then had them reconditioned and re-fitted by a joinery and foundry in Chapelizod.